Take Heart: Embodying Prayer and Discernment like a Psalmist

Photo by Serkan Göktay: https://www.pexels.com/photo/woman-standing-near-body-of-water-66758/

To prayerfully metabolize their experience and discern God’s leading, thriving Christian leaders can draw on the embodied example of Psalm 31.

For the last 10 years I have accompanied a man we will call Aaron as a spiritual director. Aaron is a white, cisgendered, mainline pastor within 10 years of retirement. [1] He brings to our conversations both a high degree of self-awareness, as well as an equally strong capacity to articulate what he is experiencing and how he is interpreting that experience. One day Aaron arrived with news of his recent heart attack. Already, he wanted to begin exploring the experience and discerning where God was leading him in its wake. Having exhibited few, if any, risk factors prior to his heart episode, Aaron found himself uncertain and disoriented. He said, “It’s going to take me a long time to metabolize this experience.”

Aaron’s mention of “metabolizing an experience” points to several essential aspects of the spiritual direction process. For example, we are hungry for the presence and movement of God in the world, we chew on those encounters through stories of human experience, we trust the Spirit to be at work in often slow and organic processes, and we keep responding through our whole being. The complexity and importance of this process, especially around an intense experience like Aaron’s, invites us to bring our fullest selves into the conversation—including our bodies. To begin turning toward experiences fully and prayerfully, directees like Aaron need a robust approach that incorporates the cognitive, affective, and bodily dimensions of human experience. Unfortunately, spiritual direction sometimes slips into an under-developed intention to “move from head to heart.”

One challenge is that listeners in formation hear the dichotomy of head/heart to be absolute. The general invitation to explore feelings as a way to lead a conversation “deeper” is helpful—if held loosely. However, this dichotomy falls short in cases like Aaron’s, when there is so much stirring in body and mind. Under this dichotomy, when head is associated with thinking and heart is equated to feeling, listeners risk prioritizing feeling to the exclusion of embodiment as a worthy dimension of human experience. Another potential limitation is dismissing the opportunity to support a person in sorting through disoriented thinking. Aaron needed a more whole-bodied approach to reflect on his heart attack in light of his relationship with God, as his prescient language of “metabolizing” suggests. Scripture holds wisdom about this. The biblical understanding of "heart," particularly as found in Psalm 31, points a way forward by incorporating thinking, feeling, and bodily sensation into the exercise of prayer and discernment.

Hebrew Notion of Heart

Setting an orientation to the biblical vision of the human person in relationship to God is foundational for understanding psalmody as a whole-bodied approach to prayer and discernment. One entry point is the language of “heart” as used in the Torah. There “heart” communicates the wholeness and commitment of the human person, centered in the chest. Ellen Davis describes the Hebrew conception of heart to be “the organ of imagination, thought, feeling, and will.”[2] Already, this interpretation reaches beyond a dichotomous notion of heart associated with affect alone, drawing in imagination, thought, and will, as well. But what about the relationship of the human person to God? Davis continues her description with an affirmation that, according to the Hebrew perspective, the heart “is also the locus of faith and personal commitment, the faculty whereby humans make a real connection with God.”[3]

With this biblical vision of heart as a guide, the Shema can now be heard in the keys of imagination, commitment, and concrete action:

Hear, O Israel: The Lord is our God, the Lord alone. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might. Keep these words that I am commanding you today in your heart. Recite them to your children and talk about them when you are at home and when you are away, when you lie down and when you rise. Bind them as a sign on your hand, fix them as an emblem on your forehead, and write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates (Deut. 6:4-9 NRSVUE).

God commands the Israelites to acknowledge the covenantal bond with a sense of completeness—loving God with whole hearts, keeping the commandment secure in the seat of their being, and translating that commitment into concrete action. In writing about the book of Jeremiah, Charles Jefferson similarly conveys the essence and intentionality assumed in this richness of biblical language: “By ‘heart’ I mean what the Bible means, an affair of the interior life, of the soul, of the innermost chamber of personality.”[4] This biblical physiology suggests that Scripture should be read in a way that does not limit language of the heart to feelings alone.[5]

Like the psalm soon to follow, Deuteronomy 6 exercises the relationship with God in embodied ways. After stating belief in the one Lord and a loving bond to the same, the words of the covenant are enacted. They are to be recited to the children (v. 7), bound on the hand (v. 8), and written on the doorposts. These examples support an important dynamic related to prayer and discernment. Because we cannot experience God apart from our human faculties, it follows that any encounter with God and any response to God must proceed through the same faculties. In verse 4, God appeals to Israel through their human capacity for listening, “Hear, O Israel.” God then asks them only for what they have to give—their complete love. God delineates what this love and commitment would look like within daily life, “when at home and when they are away” (v. 7) and placing reminders at their homes and on their gates (v. 9). All this reflects God’s appeal to the heart—in the fullest biblical sense—through the incarnational context of human experience. Therefore, as Psalm 31 will show, heart and experience remain both the departure points and means of prayer and discernment in return.

This centering of human experience, especially in connection to prayerful discernment, may raise questions for some readers. For example, how can we trust that which is apart from Scripture, tradition, and reason? Or, what theological positioning demonstrates how God moves and speaks through human faculties, and how we determine which movements are truly from God? Legitimate questions like these lie outside of the scope of this essay, but only in favor of focusing on ways to help Christian leaders move beyond a dichotomy between thinking and feeling into more fully embodied forms of prayerful consideration of their experience. If any hesitation persists about the trustworthiness of our human faculties, rest assured that the psalmists model the value of expressing the raw material of human experience directly to God in prayer.

Psalm 31 as Embodied Prayer

Psalmody is embodied through both physical action and imagery. It is possible that, through familiarity with psalms as texts, these aspects of physical engagement go unnoticed. In terms of physical action, the Psalms of Ascent (120-134) were prayed as the Israelites traveled up to Jerusalem for festivals. Likewise, the intensity of anger, sadness, and joy in psalms (e.g. Psalm 4, 9, 13, etc.) can hardly be imagined without fists, raised hands, or tears. Even the simple fact that human bodies speak and sing these hymns together means that the gathered physical community invests its God-given breath and voices to make the psalms audible.

This assertion of embodiment takes a cue from Anathea Portier-Young, who argues for increased attention to the multi-dimensional expression of the prophetic act:

While a primary emphasis on communicative, cognitive, and verbal dimensions of prophecy risks downplaying or excluding its embodied dimensions, the recognition of prophecy’s experiential, performative, and embodied dimensions helps chart a course toward a more explicitly integrative approach.[6]

Although Portier-Young is writing specifically about the prophets, the same instinct applies to the psalmist. The psalmist’s vigorous expression of prayer cannot be confined to a page any more than an entire psalm could be categorized as either thinking or feeling. Instead, a more integrative approach—one deeply informed by the Hebrew notion of heart—turns toward psalms with the expectation that they demonstrate whole-bodied prayer. What is more, the Christian tradition trusts these psalms to be formative for expressions of prayer and discernment.

In his book Just Discipleship: Biblical Justice in an Unjust World, Michael Rhodes argues that, “The Psalms give us scripts to protest to, rage at, and plead with God over injustice.”[7] Again note an intensity of prayer that could not likely escape some physical expression. Rhodes is also turning to the psalms to suggest that they offer models and scripts for encounters with God. If, indeed, a Christian leader like Aaron is coming to spiritual direction disoriented and uncertain, how can they pray? Psalms provide an outlet for thinking, feeling, and embodiment that might otherwise remain hidden away.

Psalm 31 is instructive in this multi-dimensional and “hearted” approach to prayer. A more intricate analysis of the psalm might borrow elements form Ellen Davis’s description of heart in the Hebrew conception (thought, imagination, feeling, and will). In the interest of concision, however, it is enough to say that Psalm 31 bears witness not only to thinking and feeling, but also embodiment. A few examples of each will illustrate this point:

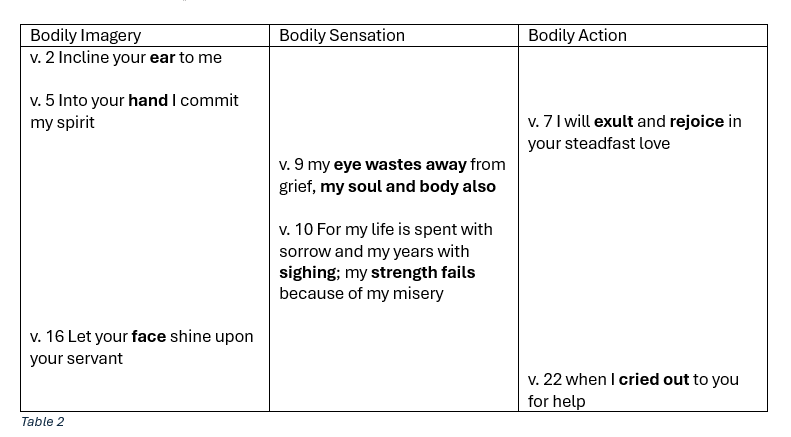

Even these few selections show the interplay between thought and affect in the psalmist’s prayer. The psalmist calls upon the Lord and cries for refuge (v. 1) and, though stated as a thought, it is clear that fear of shame lies behind that call (v. 1b). Trust is a statement of fact, but also a demonstration of will and confidence (v. 6), while the promise to exult and rejoice (v. 7) are verbs also infused with feeling. Lastly, the psalmist’s petition for grace and confession of distress (v.9) are yoked together. Nearly every line of the psalm explores the interplay between thinking and feeling in prayer, and yet these lines also integrate the bodily dimension, as well. The selections in Table 2 demonstrate this through bodily imagery, sensations, and actions:

Psalm 31 demonstrates that the psalmist incorporates significant awareness of and attention to the experience of the human body into the expression of prayer. The psalmist attributes bodily imagery to God in the pleas to “Incline your ear” (v. 2) and “Let your face shine” (v. 16), as much as in the image of taking refuge, “Into your hand” (v. 5). The psalmist describes physical sensations such as an eye, soul, and body wasting away (v. 9), along with “years with sighing” and failing strength (v. 10). Throughout the psalm, this prayer is likely embodied through physical actions accompanying exultation, rejoicing (v. 7), and crying out to God for help (v. 22).

These examples of thinking, feeling, and embodiment demonstrate that the psalmist engages in prayer directed toward God, reflects on human experience, and enlists all of their human faculties to do so. Imagine the consternation of psalmists like this one if they had been to choose only one dimension through which to pray.

Heart-full Prayer and Discernment

This survey of the Hebrew notion of “heart” and this brief review of the whole-bodied prayer offered in Psalm 31 has laid the foundation for sacred conversation that extends beyond a dichotomy between thinking and feeling. At the very least, the biblical witness affirms the importance of incorporating the whole human person—thinking, feeling, and embodiment—into prayer directed toward God. As a spiritual director working regularly with these themes, I am also convinced that we have gained insight into the faithful practice of discerning God’s presence and leading. If we are watching for God in the midst of human experience, we will perceive and respond to that presence through our human faculties. Accordingly, Aaron needed to listen for God through thoughts of disorientation, mixed feelings of gratitude and prayer, and, importantly, through a now heightened sensitivity to bodily sensations. It is to our advantage to pay attention to the full range of human experience as we practice waiting and watching for God. In fact, Psalm 31 closes with this rousing charge: “Be strong, and let your heart take courage, all you who wait for the Lord” (v. 24). That call to a courageous heart now rings out in its fullest sense, inclusive of our imaginations, thoughts, feeling, wills—and even our bodies.

As we accompany those like Aaron who are metabolizing their personal and ministry experiences, it is imperative that we foster psalmist-like attention and prayer. Rhodes writes, “The book of Psalms provides us with songs and prayers, it carries a unique power to form us for justice.”[8] Likewise, the authors of Psalms for Black Lives speak often of “building a justice imagination.”[9] These authors underscore the convictions that have led faith communities to entrust themselves to the Psalter’s formative power for millennia. Whether through daily prayer, communal liturgy, lectio divina, or other practices, we too can become immersed in the language and expressions of the Psalms. To take heart, we need only let the psalms guide us in learning and rehearsing the full breadth of human thinking, feeling, and embodiment. Then, on the hard days and the good ones, we will again turn toward God together with the fullness of human capacities that the psalmists convey.

[1] “Aaron” kindly granted his permission to share his story in service of mutual learning.

[2] Ellen F. Davis, Opening Israel’s Scriptures (Oxford University Press, 2019), 312.

[3] Davis, Opening Israel’s Scriptures, 312.

[4] Charles Jefferson, Cardinal Ideas of Jeremiah (Stratford Press, 1928), 53.

[5] Another study might just as easily explore this argument related to “soul” and “might,” as well.

[6] Anathea Portier-Young, The Prophetic Body: Embodiment and Mediation in Biblical Prophetic Literature (Oxford Academic, 2024),14.

[7] Michael J. Rhodes, Just Discipleship: Biblical Justice in an Unjust World (IVP Academic, 2023), 78.

[8] Rhodes, Just Discipleship, 76.

[9] Gabby Cudjoe-Wilkes and Andrew Wilkes, Psalms for Black Lives: Reflections for the Work of Liberation (Upper Room Books, 2022).