Andrei Rublev's Faithfulness and Creativity in the Icon of the Trinity

The experience of praying with the icon of the Trinity by Andrei Rublev is sufficiently rich in and of itself, inviting the praying believer into the ancient mystery of fellowship between the Father, the Son and the Spirit. Perhaps that is what makes the additional context from Gabriel Bunge's The Rublev Trinity (trans. Andrew Louth, St. Vladimir's Press, 2015) all the more fascinating.

Some resources examine the aspects of Rublev's icon and what meaning they might suggest. These are the basic questions of color, tone, figures and line that help us understand what the iconographer was trying to communicate through symbol. Helpful as this may be, Bunge's book takes up additional dimensions.

Where does Rublev's icon stand in the course of Christian tradition? What made Rublev's Trinity so remarkable that the Eastern Church calls it a "canonical model for the depiction of the Holy Trinity" (74)? Bunge strives to help readers understand the role a faithful iconographer plays within the development of Christian theology:

The principal task of icon painters is not to make something new that dumbfounds the beholders and leaves them often perplexed. New iconographic types--icons manifest for the first time--are rare, comparatively speaking. With church proclamation in general, which the icon painters serve in their own way, icon painters take part in the task of "keeping the good thing committed [to us]" (2 Tim 1:14). The more faithfully they do this in their time and with the resources of their time, the more selflessly they "hold fast to the traditions" received (1 Cor 11:2). The more purely they adhere to church tradition and proclamation, so much the more will they, after the example of the great teachers of the Church, paradoxically become genuinely creative. Iconographers do not change the language, which would make them altogether incomprehensible in their own time and for posterity, but they release unsuspected depths and give them expression so as to make them accessible to others. (88, adapted with inclusive language)

Bunge's contribution lies in helping the reader better appreciate Rublev's paradoxical faithfulness to the theological tradition he received and the expression of genuine creativity. The combination of the two has made "unsuspected depths" accessible to praying believers for over 500 years.

A brief survey of the icons that preceded Rublev's will help illustrate this point. Bunge argues (with appropriate nuances about the difficulty of such categorizations) that iconographers leading up to Rublev reflect three main developments in the theological interpretation of Gen. 18: angelogical, Christological and Trinitarian. These interpretations, he insists, deepen rather than replace one another. As early as ca. 350, icons that focused on Abraham's hospitality to the three visitors by the oaks of Mamre and depicted homogeneous figures as angels (see Fig. 1). As patristic theology continued to consider the relationship between the Christ of the New Testament and the began to consider Gen. 18 to be a "manifestation of Christ and hidden foreshadowing of the Incarnation of the Son," icons from about 1000 began singling out the central figure as Christ, often depicting him with a scroll or a cross in his halo(see Fig. 2). By about 1350, reflecting an increasing appreciation for the Trinitarian mystery in Gen. 18, we see Abraham and Sarah fade away while only the three figures, the table and the vessels remain (see Fig. 3).

Here enters Andrei Rublev (1370-ca. 1430), who stands on the Russian Orthodox tradition as a monk and as an icon painter. He is deeply influenced by St. Sergii of Radonezh (1314-1392), whose Trinitarian mysticism inspired both monasticism of his day and generations to follow. Nikon of Radonezh (1355-1426), Sergii's successor as abbot of Holy Trinity Monastery and rebuilder of the Church of the Holy Trinity, commissioned Rublev (and his friend Daniil) to paint the church. Rublev's icon of the Trinity was either painted at this time or earlier and then placed in the church between 1422 and 1427.

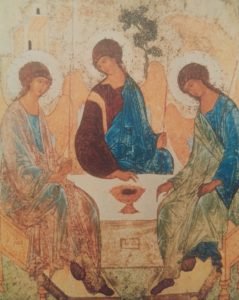

Having set some context for Rublev's icon, we come to Bunge's specific observations about Rublev's genuine creativity. Imagine the moment in prayer when, after fasting and reflection, the Spirit touched Rublev and he saw what he must express to advance the iconographic tradition which strives to make the mystery of the Trinity accessible to the praying believer. The icon that manifested (see Fig. 4) bore the following unique traits (86-87):

- The gaze of the figures moves from the central figure to the one on the left.

- The angels on the sides are now of the same size as the central one.

- The gestures relate not as much to the vessels as to the three equal persons.

- The table becomes more recognizable as an altar.

- There is no room for any figures but these three.

- The elements of house, tree and rock are reduced in size and now each related to a figure.

These elements may well be familiar to those of us who have prayed with no other icon depicting Gen. 18. Even the modern iconographer S. Mary Charles McGough OSB (1925-2007), 500 years later, would trust Rublev's expression enough to maintain these elements in the icon housed today at St. Paul's Monastery (at top). Still, thanks to Bunge, we can step back and breath deep the Christian tradition infusing this icon with centuries of praying with the Mystery of the All-holy Trinity. Then we can return to gazing upon this icon and continue pray in fellowship with the Three-In-One.

These elements may well be familiar to those of us who have prayed with no other icon depicting Gen. 18. Even the modern iconographer S. Mary Charles McGough OSB (1925-2007), 500 years later, would trust Rublev's expression enough to maintain these elements in the icon housed today at St. Paul's Monastery (at top). Still, thanks to Bunge, we can step back and breath deep the Christian tradition infusing this icon with centuries of praying with the Mystery of the All-holy Trinity. Then we can return to gazing upon this icon and continue pray in fellowship with the Three-In-One.

For further meditation . . ."A life in communion with the All-holy Trinity in and through the Holy Spirit is the meaning and end of the Christian life." (77)

"Since Easter it has been an ever-enduring Pentecost. Whoever has received the Holy Spirit (Jn 20:22), who proceeds from the Father, from the breath of the Risen One is a temple of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor. 6:19), a dwelling place of the undivided Trinity. He is, in the true sense of the word, a 'pneumatikos' (1 Cor 3:15f), whose spiritual life is hidden with Christ in God (Col 3:3)." (112)

Three-In-One: An Icon of Shared LeadershipReader's Poem: The Rublev Trinity